Sarah Buckingham discusses the reasons for conserving modern movement public housing.

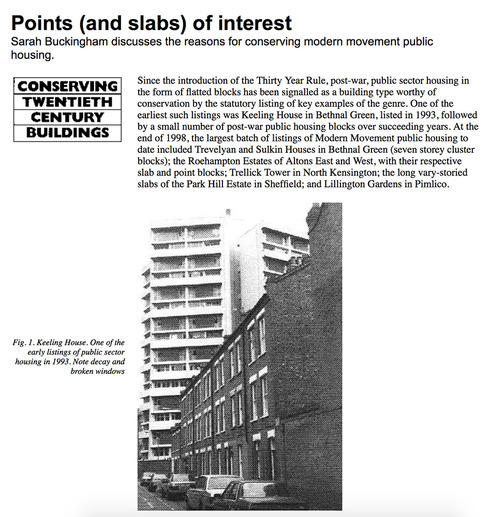

Since the introduction of the Thirty Year Rule, post-war, public sector housing in the form of flatted blocks has been signalled as a building type worthy of conservation by the statutory listing of key examples of the genre. One of the earliest such listings was Keeling House in Bethnal Green, listed in 1993, followed by a small number of post-war public housing blocks over succeeding years. At the end of 1998, the largest batch of listings of Modern Movement public housing to date included Trevelyan and Sulkin Houses in Bethnal Green (seven storey cluster blocks); the Roehampton Estates of Altons East and West, with their respective slab and point blocks; Trellick Tower in North Kensington; the long vary-storied slabs of the Park Hill Estate in Sheffield; and Lillington Gardens in Pimlico.

These estates and blocks are undoubtedly paradigmatic examples of architectural and historic interest of national significance; however, the controversy with which successive tranches of listings have been greeted has been publicly and sometimes heatedly aired, and reflects the mixed reception that such blocks have had since their inception. The problems that the group as a whole is perceived to pose concern their often unwelcoming appearance, unfortunate contribution to the townscape, and their unsuitability as a living environment for an often unwilling population.

These, may, indeed, be substantive problems, presenting conservation practitioners with the apparent paradox of a developing interest in conserving the special qualities of examples of a building form in which, at best, these very qualities may render it unpopular, and, at worst, may be the instruments of its significant functional failure. So, as these listings are becoming accepted, if not universally welcomed, it is, perhaps, time to consider this distinct and peculiar category; the implications of listed status for their role in the realm of public housing; and to consider whether they require any special approach to maintain them as examples of fine architecture and manifestations of the political, social and architectural ideology of their time.

Detailed consideration of the practicalities of conserving and managing such blocks was based on three examples: Goldfinger's mighty tour~de-force, Trellick Tower in North Kensington (completed 1972); its close cousin Balfron Tower in Poplar (completed 1967); and Lasdun's innovative cluster block, Keeling House, in Bethnal Green (completed 1959). Some new challenges were revealed, while others, more familiar, were recast in a novel setting. The major issues can be summarised as follows.

Preservation of character

The special architectural character of these buildings was determined by design and construction choices influenced by the tenets of the Modern Movement: huge dimensions and monumentality of scale, Spartan plainness, and a regular repeated grid of beams, balconies or fenestration are common features. Such design choices have created common perceptions of an unfriendly, unreadable, indeed impersonal environment.

Problematic design elements include: lifts and lobbies used by large numbers of people; pilotis or integrated garages, raising the blocks above ground level and limiting surveillance of entrances; estate layouts with no street pattern, comprising randomly disposed blocks in open areas; the presence of raised walkways linking blocks; unsupervised facilities such as play areas or communal garages. All these are likely to increase opportunities for and temptations to abuse.

Thus preservation of special character will have to be carefully weighed against concerns about the quality of life of residents, and any changes must carefully attempt to reconcile these sometimes conflicting concerns. Examples where this has been successfully negotiated include the introduction to Trellick Tower of a concierge and faster lifts with integral security devices, alongside reinstatement of the lobby, including Goldfinger's trademark stained glass work.

Management Plans can potentially play an important role in protection of character by clarifying for residents the acceptability of minor personalising changes to interiors; knocking through between adjacent lavatories and bathrooms; window replacements; installation of satellite dishes, etc.

Physical deterioration

Expediencies of cost and speed, plus aesthetic decisions, sometimes resulted in the choice of relatively untried construction techniques and materials for these blocks, with ramifications for the appearance, weathering capacity, or even stability of the blocks in the long term. For example, the almost ubiquitous reinforced concrete was quick to lose its pristine appearance in favour of dull, rainstained drabness; while leaking of joints between cladding panels or water ingress on flat roofs are all prob- lems commonly associated with modern flatted blocks.

In Keeling House, for example (Fig 1), the original construction has not stood the test of time: the concrete was poorly mixed and compacted, leading to localised admixtures of salt, porosity, and subsequent decay of the inadequate covering to reinforcing rods. Chunks of cladding spall away as the rods rust. This effect, compounded by a lacklustre maintenance programme by the local authority, was the cause of the building being vacated, standing empty for several years during which time it was under serious threat of demolition, despite its listed status. Listing and the eventual sale of the block to a private developer for refurbishment have pulled it back from the brink, and an extensive programme of concrete repair is underway at the time of writing. Patch repairs of the original raw concrete finish, which is to receive a protective coating, is a necessary compromise in securing the future stability of the fabric and enabling renewed use.

Functional success

Although post-war flatted blocks were initially fully occupied by those displaced from the 'slums' they replaced, physical deterioration led to a process described in detail by Anne Power and other commentators; in a nutshell: abandonment by the more economically successful; creation of high void levels leading to 'hard to let' areas which, with continuing pressure for social housing in the 1970s and 1980s, were filled with the most vulnerable, socially and economically powerless families. Voids and failure to collect rent arrears lessened income for routine maintenance or improvements to estates, thus fuelling the conditions that had caused their unpopularity in first place. Created in the belief that they would let new communities develop and grow, Modern Movement public housing had, in fact, been instrumental in dispersing localised, close knit communities, relying on inter-personal relationships, while ensuring that new relationships had little opportunity to be established. Insecurity and discontent were often manifested in an unfriendly and vandalised environment.

In the 1970s Trellick Tower (Fig 2) went through a pronounced phase of antisocial and criminal behavior ur including vandalism, arson, physical intimidation, even attack, of residents, and regu- lar burglary of flats. in addition to attempts to introduce effective security measures, the borough introduced a new lettings policy, under which only those who wished to be were housed in the block. The result was the creation of a more stable community, who want to live in the Tower, and a drastic reduction in crime and abuse against people and property.

This illustrates that the mitigation of social problems in a block requires a number of prerequisites to succeed, prime among which are development of a sense of community and removal of fear by the installation of effective security measures. Considerable involvement, too, is required on the part of key members of the local community, involved in the running of the block itself or in the mechanisms of the Tenants' Management Organisation (TMO) which runs public housing in the borough.

Setting

Modern movement housing blocks and estates were intended to stand proud from the older surrounding townscape and, indeed, succeed in this admirably (Fig 3). In a modern, heterogeneous and robust city, theirs can be a positive impact - both Balfron and Trellick Towers lend distinction to areas generally characterised by less visually stimulating modem blocks, while Keeling House stands out in worthy contrast to older patches of townscape.

On the other hand, their immediate surroundings - subsidiary structures or open areas originally intended for recreation and socialisation - may provide particular problems with implications for the setting of the block or blocks. Initiatives resorted to in nonlisted estates include demolition of structures or enabling developments on open spaces. For Balfron Tower, associated blocks by Goldfinger and open estate land relating to them have been included in a conservation area intended to protect the setting of the listed block. For Trellick Tower and Keeling House, similar measures are under active consideration, subject to consultation with affected parties.

Funding

The owners of these blocks - normally local housing authorities - are famously hard pressed for funds, which, often taken with a legacy of unsystematic maintenance over a long period, may lead to the stockpiling of problems. in the case of Trellick Tower, considerable investment has been made by the borough and the TMO to achieve its currently popular and successful status. Keeling House, meanwhile, proved beyond the means of the local authority, and was sold on to a new, private owner, which is now investing in its refurbishment for sale of the flats on the private market. For Balfron Tower, yet another course of action is being pursued: the recent award of a Townscape Heritage Initiative grant scheme from the Heritage Lottery Fund is to be matched by the local housing authority to create a fund of up to £2.4 million to secure changes to the fabric of the block and facilities of the Brownfield Estate conservation area in which it stands.

The future

Listed Modern Movement blocks of social housing illustrate the perennial concern of retaining listed buildings in beneficial use as a means of securing their continued existence. in this case the housing must evolve to meet the new standards and demands of a changed society, and provide appropriate, attractive, successful dwellings. This will inevitably present the landlord/owner with a significant financial commitment.

There is no quibble about the good standard of accommodation generally provided inside these blocks, in flats which often enjoy the advantages of good space standards, good proportions, favourable orientation, generous balconies, and large windows. Once crucial issues such as security within the block and establishment of an appropriate lettings policies have been addressed, these advantages can be appreciated to the full by its residents.

With the deterioration of a block's physical condition comes an increased threat of demolition, and with that a diminishing chance of retaining a social housing use: when Keeling House was at its nadir, the dependence on external grant funding for repairs was so high that no viable rescue package could be drawn up which retained a social housing use. With the involvement of private finance - aimed ultimately at securing a satisfactory financial return on the project - comes increasing pressure for change in the intensity of use and to the fabric of the building. This has been successfully negotiated in the case of Keeling House, with the creation of two new units in ground floor areas and the addition of a lobby being the major changes.

Associated facilities such as multistorey or underground car parks, community spaces, open areas can be a great resource for the Modern block or estate. With careful consideration and investment they have the potential to be developed as community facilities, or training, employment or revenue generating uses.

It is, perhaps, the intensity of the need to secure their successful functioning, and the directly harmful effects of failing to do so that sets these listed buildings apart from other categories. If they fail to provide successful housing, they will undergo abuse to their fabric, lessening the resources to deal with maintenance issues. With physical deterioration will come the stigmatisation of the block, stimulating more abuse. The preservation of their fabric and character will, perhaps rightly, receive a low priority; funding for reinstatement works will fail to materialise; surviving or replaced original features are unlikely to be respected. Trellick Tower illustrates the successful rehabilitation of such a block, retaining its social housing use, and is a token of optimism that similar about-turns can be effected elsewhere. For the conservation practitioner, this may entail greater awareness of, indeed involvement in, multi-agency initiatives to support and sustain block or estate communities.

Sarah Buckingham is Conservation Officer at the London Borough of Tower Hamlets where she has worked for ten years.