I have included excerpts below but encourage you to visit the website to see the full article and accompanying images.

Building of the month, Twentieth Century Society, Laura Chan

The tabula rasa caused by the Blitz allowed the London County Council (and later the Greater London Council) to embrace the ideal of concentrated living, an anti-utopian model.

Over the course of the 1950s to the 1970s, modern architecture spawned Brutalism, an aesthetic that was adopted by Poplar in the East London borough of Tower Hamlets, with Balfron Tower and its neighbouring Robin Hood Gardens estate. Commonly dubbed the “younger sister” of Trellick Tower, Balfron Tower is due for renovation next year, before which residents will have to vacate their properties. Designed by Erno Goldfinger and built in 1967, Balfron gained Grade II listing in 1996.

Goldfinger intended to underscore fluid movement in both towers by separating the services shaft from the main residential block and connecting them with suspended walkways or ‘streets in the sky’. With these raised walkways, Goldfinger sought to construct a romantic image of moving relationships, chance encounters and neighbourliness; a core ambition of Brutalism, further demonstrated by its structural honesty in the continuation of materials from interior to exterior.

Designed as an ‘ordered shell’, Goldfinger’s towers play a vital role in what he called ‘the human drama’. Like dancers, Goldfinger saw people as ‘time and space bound’, always enclosed by space, even if this sense of enclosure was conveyed by the sky. Writing extensively on the emotional effect of architecture, Goldfinger suggested that we are aware at some level of the way space encloses, that “you are in the street even if you are out of doors”.

Within his high-rises, human movement stops in waiting for the lift – and as Balfron only has two, people are often subjected to long delays. But once inside, the building takes over the dance. Upon entering, the vertical ribbon windows indicate the movement inside the services tower, of the up and downward motion of the lifts. When the desired floor is reached, the horizontal glazing corresponds with the direction of travel across the walkways leading to the dwellings. In this way, the building can be seen as more than a passive receptor for circulation, as it echoes the movement of the body.

In 1968 Goldfinger moved into flat 130 on the top floor, where he and his wife hosted parties fuelled with champagne, where residents were invited to discuss their flats and how they could be improved. Equipped with this knowledge, Goldfinger went onto design the taller and more famous Trellick Tower in West London. As such, the spatial design of Trellick is a further continuation of inhabitants’ movements. Doors slide into walls, rooms partition into different spaces and windows rotate for cleaning – an appropriation of space is acquired by both body and architecture in a dynamic display; the dance of the everyday.

Having lived in Balfron myself in 2010, I know all too well the downsides of living in a 1960s concrete high-rise: cockroaches live behind the concrete panels; the complex water system means you never quite know where the leak in the toilet is coming from; when both lifts break down there’s a long walk ahead of you. Maintenance issues aside, it was an absolute joy to live on the twenty-first floor of the magnificent Balfron. From this height, London was in the cup of my hands, my eye-line at the same level as the horizon.

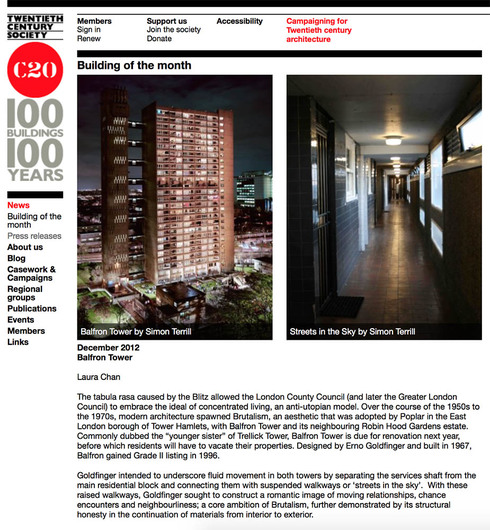

While living there I took part in Simon Terrill’s grand photographic project involving Balfron and its residents. The artist-in-residence used a large-format camera and flooded the tower with stage lighting, signalling when each shot was being taken with sound cues. He explains, “Each exposure lasted for 10 seconds and so with the opening of the lens, a strange stillness came over the building as movement would result in blurred erasure and those present needed to be stationary in order to remain visible.”

Terrill captures Balfron Tower in a glorious eerie hue, and when looking at his work I hark back to the days when I used to wait for the lift, before the dance had begun – for it to take me up, for my journey’s end was only reached when I’d crossed the twenty-first street in the sky.

Owen Hatherley, The myth that Canary Wharf did east London any good, The Guardian

There are few places so utterly implicated in our discontents as this symbol of the ludicrousness of 'trickle-down' economics

Canary Wharf, the "second City", an "evil twin" to London's financial district, has overtaken its ancient rival, according to the Financial Times. It wouldn't be altogether surprising if some saw this as a cause for celebration. Canary Wharf, and the 1980s Docklands development of which it was the most successful part, was an enterprise zone, an idea that the current government is trying to revive.

As an enterprise zone it was deliberately unplanned, low-tax, and in theory low on "big government", except for the not-so-small matter of massive public investment projects such as the Docklands Light Railway or the cleaning, dredging and decontaminating of the old industrial sites. Regardless, if it has "worked", then surely the coalition's new zones can point to it as some kind of model. One form of industry, the dock labour of the Port of London, was replaced with another, financial services. Around 80,000 jobs in the former, 150,000 in the latter. What could possibly be wrong with this?

Everything. Canary Wharf has been for the last 20 years the most spectacular expression of London's transformation into a city with levels of inequality that previous generations liked to think they'd fought a war to eliminate. Very, very few of the new jobs went to those who had lost their jobs when the Port of London followed the containers to Tilbury; those that did were the most menial – cleaners, baristas, prostitutes. The new housing that emerged, first as a low-rise trickle in the 80s and 90s followed by a high-rise flood in the 00s, was without exception speculatively built. Inflated prices, dictated by the means of a captive market of bankers, soon forced up rents and mortgages in the surrounding areas, a major cause of London's current acute housing crisis.

Looked at in the long term, Canary Wharf is the final victory of "old corruption", the financier-rentier capitalism centred on the City and landowners over industry, literally building its new edifices on top of spaces formerly devoted to manual labour and working class organisation. Thatcherites, early on, liked to think their race-to-the-bottom policies on wages and unions might rejuvenate British industry, but Canary Wharf is the place where that was shown up for the myth it always was. Instead, old money got computers, built itself glass skyscrapers, hid its old-school ties and transformed itself into a gigantic offshore money-making mechanism.

The ludicrous nonsense of "trickle-down economics" is exposed in Canary Wharf more than anywhere else in Europe. A 10-minute walk away is Balfron Tower, a listed, proud but under-maintained tower of council housing, designed by the architect Erno Goldfinger, currently owned by a housing association. Recently it emerged that renovations there would have to be paid for by selling the flats on the open market. There was no other way of raising money, apparently. And just opposite is some of the most apparently overflowing wealth in world history. Around Balfron Tower you can find the largely low-rise Lansbury estate, built as part of the Festival of Britain, similarly covered in grime and pigeon shit and beset by rampant unemployment; or Robin Hood Gardens, where an architectural hoo-ha over impending demolition has masked another incursion of Canary Wharf's bankers and its values into the area. If anyone in any of these estates has seen anything trickle down it would be an unpleasant-smelling liquid running from a great height.

So how has the myth that this place has done anything for east London other than compounding its misery managed to endure? How, with this massive counter-argument against trickle-down, have similar projects from Manchester to Portsmouth managed to hold it up as a model? Perhaps it's just the sheer visibility of Canary Wharf, its seductive size and shininess, its malignant growth. It had a false start, and for years, "Thatcher's cock" stood tumescent but alone.

It was really New Labour that was intensely relaxed about the place, with most of the skyscrapers dating from the 2000s, the years in which it became something yet more malevolent. In a piece published at the start of the financial crisis, the late political essayist Peter Gowan called it "Wall Street's Guantánamo", the place where the likes of Lehman Brothers could escape the relative rigours of US law and fully indulge in the fictitious capital of credit default swaps and collateralised debt obligations. There are few places on earth so completely and utterly implicated in our current discontents, or anywhere so due a serious reckoning. Somehow, rioters missed it last August, the barrier of the arterial road that severs it from Poplar perhaps seeming impassable. Maybe they'll reach it next time.

Building of the month, Twentieth Century Society, Laura Chan

Having lived in Balfron myself in 2010, I know all too well the downsides of living in a 1960s concrete high-rise: cockroaches live behind the concrete panels; the complex water system means you never quite know where the leak in the toilet is coming from; when both lifts break down there’s a long walk ahead of you. Maintenance issues aside, it was an absolute joy to live on the twenty-first floor of the magnificent Balfron. From this height, London was in the cup of my hands, my eye-line at the same level as the horizon.